The

invention of the submarine was one of the key turning points in naval

history as well as world history. It played an integral part in World

War II history, on both sides, and during the Cold War, submarines were

one of the greatest deterrents to World War III.

It

all began 154 years ago in the New Orleans area with a St. Tammany

resident, Horace Lawson Hunley, designing it, building it, and testing it locally. The first one he built was the PIoneer, and the third one he built was the Hunley.

No one knows where the Pioneer wound up but the Hunley was found 22 years ago off the coast of Charleston, SC.

Mandeville

resident John T. Hunley (shown above) said he wasn't related to Horace Lawson Hunley,

but he studied the invention of the submarine extensively and was

considered an excellent source of information on H. L. Hunley and his

efforts to build the world's first underwater sea vessel. He was president of the "Raise the Hunley" organization.

Below is an

article he wrote in 1992 about the first prototype, the Pioneer. Click on the image to make it larger.

Then, a couple of years later, in 1995

Here is his article. Click on the image to make it larger.

When the third submarine prototype built by Hunley was found offshore at Charleston, S.C., in 1995 John T. Hunley of Madisonville started the "Raise The Hunley" organization that was based in Madisonville, with himself as president.

That year he traveled to New Orleans to meet with a friend of his, the acclaimed adventure novelist and marine researcher Clive Cussler. They discussed the recent discovery of the lost submarine "The Hunley," and how efforts were being planned to raise the historic vessel that rewrote naval history in Charleston, SC.

I was privileged to take pictures of this group and hear their amazing story as they tracked down the final resting place of The Hunley submarine, the world's first successful submarine, according to documents that detail the inside mechanisms and historic accounts that credit the vessel with sinking a ship on its own.

Click on the images of the article below to read more about this real-life adventure.

Photos by Ron Barthet

Clive Cussler and John Hunley in 1995

Horace Lawson Hunley owned a plantation in Covington and served as a state legislator and as the deputy customs collector in New Orleans, according to the Friends of the Hunley, a South Carolina commission set up to preserve the submarine. For some time, the last will of Hunley was lost to St. Tammany public records even though it had been seen and photographed in the St. Tammany Parish Archives years earlier.

Here is an article about the search for the will.

The will was found ten years later in a box that had been taken from the parish archives.

For more information about the Hunley will and what it contained,

CLICK HERE for a photo album of scanned pages from a report describing that will in detail.

INTERESTING LINKS:

For more information about the Hunley will and what it contained,

CLICK HERE for a photo album of scanned pages from a report describing that will in detail.

INTERESTING LINKS:

Click on the video above for an inside look at the submarine, courtesy of the "Friends of the Hunley" website.

According to information from the Hunley.org website, the builders of the Hunley submarines were James McClintock and Baxter Watson, partners in a steam gauge manufacturing business in New Orleans. "By late fall of 1861, these two inventors began the construction of a three-man underwater boat."

They joined forces with Horace L. Hunley, a native of Tennessee. Hunley was a lawyer, merchant, and a successful Southern planter, but his main interest was in designing and building a submarine.

"Hunley recognized the importance of breaking the Union blockade and keeping supply lines open to the South. The small band of Confederates began work on a new approach to naval warfare, one that took the fight below the water’s surface. This quest became a process of innovation and evolution," the Hunley.org website goes on to relate.

"Working with Hunley and Watson, McClintock developed two prototype submarines, the Pioneer and the American Diver. Improving the concept each time, they finally had success with the creation of the Hunley, a weapon that would forever change naval warfare.

Early Pioneer

"The Pioneer was built in New Orleans in early 1862 and performed moderately well. The small submarine would sometimes become caught at the bottom of Lake Pontchartrain with the crew cranking the propeller, unaware they were stuck. After only a short month of tests, the Pioneer was destroyed by the Confederates to avoid capture by the Union army that was quickly closing in on the city.

"Union occupation forces were entering New Orleans when the three inventors, carrying blueprints, diagrams and drawings, fled to Mobile, Alabama, with the intent of designing an even more formidable submersible attack boat.

"Soon after arriving in Mobile, McClintock, Watson, and Hunley teamed up with Confederate patriots Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons, owners of the Park & Lyons machine shop. Within months after Hunley, McClintock, and Watson arrived to the besieged and blockaded Alabama coast, a second submarine was already under construction at the Park and Lyons shop near the harbor. McClintock, in a post-war letter wrote, “We built a second boat at Mobile, and to obtain room for machinery and persons, she was made 36 feet long, three feet wide and four feet high. Twelve feet of each end was built tapering or molded, to make it easy to pass through the water.”

"During this time frame, the group began to receive local military support. Lieutenant William Alexander, CSA, of the Twenty-First Alabama Volunteer Regiment, was assigned to duty at Park & Lyons.

"The group of engineers made several attempts at propelling the new sub with an electric-magnetic engine or a small steam engine. Unfortunately, they were unable to produce enough power to safely and efficiently propel the submarine. This “trial and error” process took place over a period of several months until they decided to stick with a more conventional means of propulsion. They installed a hand crank and, by mid-January 1863, the American Diver was ready for harbor trials.

They joined forces with Horace L. Hunley, a native of Tennessee. Hunley was a lawyer, merchant, and a successful Southern planter, but his main interest was in designing and building a submarine.

"Hunley recognized the importance of breaking the Union blockade and keeping supply lines open to the South. The small band of Confederates began work on a new approach to naval warfare, one that took the fight below the water’s surface. This quest became a process of innovation and evolution," the Hunley.org website goes on to relate.

"Working with Hunley and Watson, McClintock developed two prototype submarines, the Pioneer and the American Diver. Improving the concept each time, they finally had success with the creation of the Hunley, a weapon that would forever change naval warfare.

Early Pioneer

"The Pioneer was built in New Orleans in early 1862 and performed moderately well. The small submarine would sometimes become caught at the bottom of Lake Pontchartrain with the crew cranking the propeller, unaware they were stuck. After only a short month of tests, the Pioneer was destroyed by the Confederates to avoid capture by the Union army that was quickly closing in on the city.

"Union occupation forces were entering New Orleans when the three inventors, carrying blueprints, diagrams and drawings, fled to Mobile, Alabama, with the intent of designing an even more formidable submersible attack boat.

"Soon after arriving in Mobile, McClintock, Watson, and Hunley teamed up with Confederate patriots Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons, owners of the Park & Lyons machine shop. Within months after Hunley, McClintock, and Watson arrived to the besieged and blockaded Alabama coast, a second submarine was already under construction at the Park and Lyons shop near the harbor. McClintock, in a post-war letter wrote, “We built a second boat at Mobile, and to obtain room for machinery and persons, she was made 36 feet long, three feet wide and four feet high. Twelve feet of each end was built tapering or molded, to make it easy to pass through the water.”

"During this time frame, the group began to receive local military support. Lieutenant William Alexander, CSA, of the Twenty-First Alabama Volunteer Regiment, was assigned to duty at Park & Lyons.

"The group of engineers made several attempts at propelling the new sub with an electric-magnetic engine or a small steam engine. Unfortunately, they were unable to produce enough power to safely and efficiently propel the submarine. This “trial and error” process took place over a period of several months until they decided to stick with a more conventional means of propulsion. They installed a hand crank and, by mid-January 1863, the American Diver was ready for harbor trials.

"The American Diver, according to McClintock, was “unable to get a speed sufficient to make the boat of service against the vessels blockading the port.” Despite the American Diver’s apparent limitations, evidence exists that indicates she left from Fort Morgan sometime in mid-February and attempted an attack on the blockade. The attack was unsuccessful.

"Soon after, another attack was planned, but as she was being towed off Fort Morgan at the mouth of Mobile Bay in February of 1863, a stormy sea engulfed the American Diver. Fortunately, no lives were lost.

"The American Diver was never recovered, and her rusting hull may still remain beneath the shifting sands off the Alabama coastline. Her exact location was long ago lost by history."

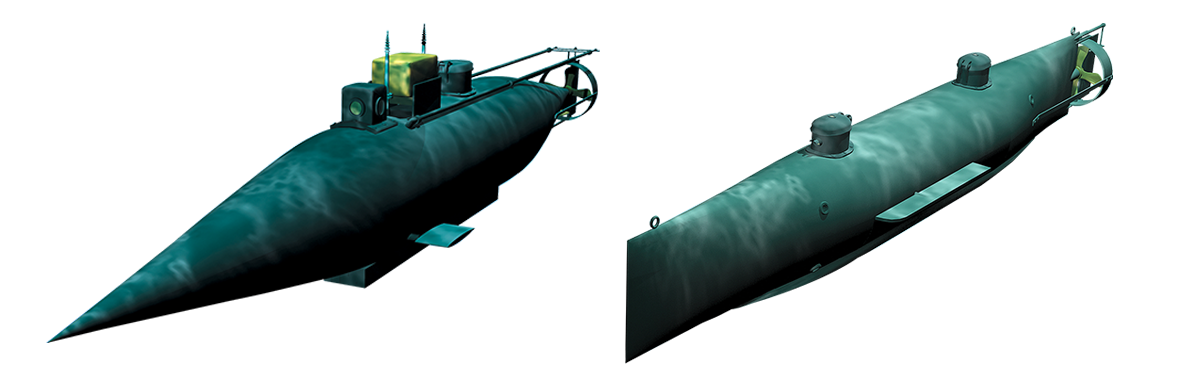

The Pioneer and the American Diver

(Images from the Hunley,org website)

(Images from the Hunley,org website)

The third submarine, the Hunley, once recovered off the coast of Charleston, has become the focal point of a large interactive museum in Charleston, with extensive displays, historical artifacts, and the Hunley itself, resting in a tank of water and carefully being examined and restored. The museum is located at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, 1250 Supply Street (on the old Charleston Navy Base in North Charleston, South Carolina.

John Hunley, standing second from right, with board of

Lake Pontchartrain Basin Maritime Museum

Photo by Ron Barthet

Clive Cussler died at 88 years of age in February of 2020, after having been confirmed as the true finder of the sunken Conferate submarine off the coast of Charleston, S.C. The Associated Press described him as "the million-selling adventure writer and real-life thrill seeker who found the Confederate-era submarine H.L. Hunley.

Beginning in 1965 Cussler started his writing career, publishing his first "Dirk Pitt" adventure novel in 1973, according to his website's biography. His efforts in trying to find sunken vessels around the world resulted in the discovery of more than 60 shipwrecks. He was founder and chairman of the National Underwater and Marine Agency.

NPR's NOVA Online Information

On a webpage entitled "400 Years of Subs" the National Public Radio network detailed what their researchers had found regarding the invention and gradual improvement of submersibles. Here is their account of the progress from the very beginning.

Civil War-era submarine

A Civil War-era submarine that was long thought to be Pioneer but is not was discovered and raised in 1878 and is on display at the Louisiana State Museum. Its true origin remains a mystery.

1861

Early in the Civil War, the Confederate government authorized citizens to operate armed warships as 'privateers.' A New Orleans consortium headed by cotton broker H.L. Hunley gained approval for the operation of Pioneer, a 34-foot-long submarine designed and built by James McClintock. The boat held three persons, one to steer and two to crank the propeller.

In a March 1862 demonstration on Louisiana's Lake Pontchartrain, a submerged Pioneer sank a barge with a towed floating torpedo. In April 1862, the U.S. Navy captured New Orleans, and its builders scuttled Pioneer. Soon discovered, the boat was sold for scrap in 1868.

The Alligator

1861

Villeroi obtained a contract from the U.S. Navy for a larger submarine, the 46-foot-long Alligator. Its propulsion was originally 16 oarsmen with hinged, self-feathering oars, but an improved version had a three-foot-diameter, hand-cranked propeller. Weapon: an explosive charge that a diver would set against an enemy hull. Alligator entered service on June 13, 1862, the first submarine in the U.S. Navy. Towed south from Philadelphia for operations in the James River, the boat proved too large to hide and support divers in the relatively shallow water, and it foundered and sank in a storm in 1863.

David

Despite its hopeful name, the David met with little success.

1863

In Charleston, a team comprised of Dr. St. Julius Ravenel, David Chenoweth Ebaugh, and William S. Henery created the low-freeboard steamboat known as David (as in David and Goliath). It could either directly ram an enemy vessel or make use of a spar torpedo, an explosive on the end of a long pole. Spearheaded by Army Captain F. D. Lee, the Southern Torpedo Boat Company built several as a profit-making venture (anyone who could sink a blockading Union warship could earn substantial bounties).

American Diver

1863

Hunley's New Orleans consortium shifted operations to Mobile, Alabama, and built a second, slightly improved submarine, which may have been called American Diver. McClintock spent a lot of time and money trying to replace hand-cranking with some sort of electrical motor, but without success. This submarine sank in rough weather in Mobile Bay; the crew was rescued.

Civil War drawings

These drawings were made sometime after the Civil War from information provided by W.A. Alexander, one of the original builders.

1863

Hunley's consortium built a third submarine about 40 feet long. Crew: probably nine, eight to crank the propeller and at least one to steer and operate the sea cocks and hand pumps to control water level in the ballast tanks.

The Confederates sent the submarine to Charleston to try to break the Federal blockade. It sank almost immediately, perhaps swamped by the wake of a passing steamer, and some crew members were lost. Confederate Commanding General P.G.T. Beauregard became disenchanted, but Horace Hunley persuaded him to allow "one more try" under Hunley's personal supervision. The boat sank again, killing Hunley and the crew.

CSS H.L. Hunley

CSS H.L. Hunley, recovered after a fatal accident and awaiting a "go-no go" decision by Charleston-area commanding General P.G.T. Beauregard.

The boat was found and raised, and two members of the original team who had not been aboard when it sank harassed Beauregard often enough that, after "many refusals and much discussion," he agreed to allow one more attempt, but not as a submarine. Now named CSS H.L. Hunley in honor of her spiritual father, the boat would now bear a spar torpedo and operate awash as a David.

Intelligent Whale

Intelligent Whale is now an exhibit at the National Guard Militia Museum of New Jersey, in Sea Girt, N.J. It was never a serious contender in the submarine sweepstakes.

1863

A group of Northern speculators formed the American Submarine Company to take advantage of a vote in the U.S. Congress to approve the use of privateers. However, when President Abraham Lincoln declined to accept the authority, construction of this consortium's submarine, the Intelligent Whale, languished. The boat was not completed until 1866, long after the war ended. The then ostensible owner, O.S. Halstead, made several efforts to sell it to the government, and the U.S. Navy finally held formal acceptance trials in 1872. The Intelligent Whale failed. Halstead was not present, having been murdered the year before by his mistress's ex-lover.

1863

The French team of Charles Burn and Simon Bourgeois launched Le Plongeur (The Diver). It was 140 feet long, 20 feet wide, and displaced 400 tons. Power: engines run by 180 pounds-per-square-inch compressed air stored in tanks throughout the boat. To operate it, crew members filled ballast tanks just enough to achieve neutral buoyancy, then made adjustments with cylinders that they could run in and out of the hull to vary the volume (Bourne's concept). Le Plongeur proved too unstable: A crew member's movements could send her into radical gyrations.

1864

On February 17, after months of training and operational delays, the spar-torpedo-armed CSS H.L. Hunley attacked the USS Housatonic, which bears the dubious distinction of being the first warship ever sunk by a submarine. Shortly after the attack, Hunley disappeared with all hands, not to be found until 1995 (by a team led by the author Clive Cussler), about 1,000 yards from the scene of action. With hatches open for desperately needed ventilation, the boat may have become swamped by the wake of a steamer rushing to the aid of the Housatonic. In summer 2000, Hunley was recovered and is now undergoing conservation and study.

1864

Wilhelm Bauer, a visionary ahead of his time, proposed powering submarines with internal combustion engines. All told, he spent 25 years developing (or at least proposing) submarines on behalf of six nations: Germany, Austria, France, England, Russia, and the United States. His plebeian origins and autocratic style, not to mention his lowly army rank, proved serious handicaps in dealing with the aristocratic brethren who ran most of the navies of the day. Essentially ignored by his native Germany in his lifetime, Bauer became a posthumous hero in the Nazi era.

1867

English engineer Alfred Whitehead developed a self-propelled mine, which he called the "automobile torpedo." This was the true ancestor of the modern submarine-launched torpedo.

1869

The U.S. Navy began manufacturing the Whitehead torpedo for use by both surface ships and a new class of vessel: the torpedo boat. This spawned the development of another new class, the torpedo-boat destroyer. Some navies flirted with yet another class, the destroyer of torpedo-boat destroyers. Whatever, surface-launched torpedoes had marginal military effectiveness and found their true home underwater.

1870

French novelist Jules Verne brought submarines to full public consciousness with Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, in which the despot Captain Nemo uses his submarine Nautilus to sink, among others, the then fictional USS Abraham Lincoln. Verne's research was impeccable: He even computed the compressibility of seawater—'0' for most purposes—to be a factor of .0000436 for each 32 feet of depth.

See also: